- Introduction

The role of women has changed dramatically over the last decades, giving them more freedom in the Western Culture. How was this in Upper Canada? Were there any differences? After all, it was a new world – did the inhabitants bring all their values with them or did they create a new society? In this paper the women’s social life in Upper Canada, pre-confederation, will be examined, taking a closer look at amusements of that time to show the different roles of men and women. First, the society in general will be described, then the amusements of that time and finally how these reflect in women’s daily and social life.

- Upper Canada’s Society

How did the inhabitants of Upper Canada live? Let us first take a look at the population numbers and the development of the province of Upper Canada. From 1790, when it was established, until 1840 it was a ‘’predominately […] rural community, residents’ lives were dictated by the need to clear the land and by the seasonal rhythms of planting, tending, harvesting, and marketing their crops’’ ¹. By 1800 many more new villages developed, bringing advantages with them, like ‘’at least one general store and a tavern; most had a market, and all soon had a church, a school, and a number of small shops and businesses’’ ². Some settlements developed from rural communities to urban cities, for example Kingston. By 1840 the population of Upper Canada had increased to 425,000 ³.

There were big economic differences between the rural families. While some did not depend on working the land for their existence, others never succeeded to accomplish more than just ‘’a subsistence level of existence’’ ⁴. The daily work was divided between women and men. Men would hunt and work the fields, while women would keep the home, raise the children and provide food and clothing. While the men took care of the heavy work, women would take care of the goods and services for their families ⁵. The roles of women and men were traditional ones and a clear distinction was made in their daily lives.

- Women’s Social Life

As it was said in the previous section, the daily work in Upper Canada was divided between women and men. The first changes to women’s daily life and role came in the early 19th century: ‘’Although women continued to bear the responsibilities of reproduction, colonial leaders began to assert that women also had a special duty to promote certain social and moral values within their communities’’ ⁶. Husbands, fathers and men in general were superior to women and a number of factors shaped a woman’s life: ‘’their sex, where they lived, the economic and social circumstances of their families and, to some degree, when they arrived in the colony’’ ⁷. A woman’s occupation was shaped by the status of the male head of her family, as the inhabitants of Upper Canada strongly believed in social hierarchy. There was a proverb describing the life of women: ‘’A woman’s work is never done’’ ⁸ and this can be seen in the way the majority of women spent their days. In this section, the daily life of women will be examined to see how this affected their social life and what amusements they enjoyed. Given the different tasks and responsibilities in the daily life of men and women, was there a distinction in their social life as well?

During the 1830s and 1840s most rural women did not enjoy the benefits of the urban development of some settlements. This was mainly because they were too far away and the roads were bad. Also, they were needed as working forces on the land. However, only those in the furthest regions did not have any regular contact with town life ⁹.

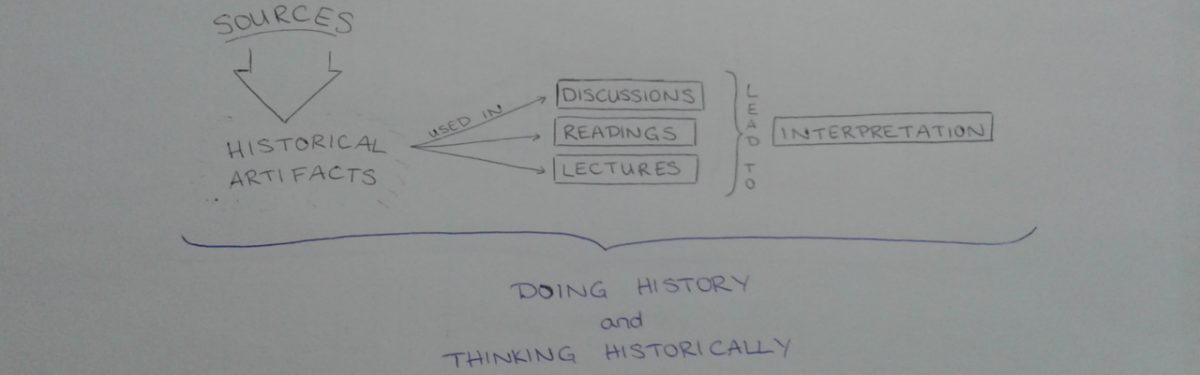

The social life of the towns was similar to English towns and ‘’Amusements of that day depended largely upon individual effort, or upon arrangements made by small groups of social equals.’’ ¹⁰. The social life here often centred around taverns and inns where lectures and dramatic readings were popular entertainment programs. These were often planned and organized by the church ¹¹. The keepers of inns were often quite important in the society, as they also had other functions – for example that of a banker. After her husband’s death, a wife would often keep the inn and become the hostess ¹². This shows that women were not completely dependent on their husbands, and that they could make a living on their own.

In the rural areas, there were some religious groups, like the Quakers, whose beliefs did not allow any amusement. Here, social life centred on the church ¹³. However, not all inhabitants were this strict. Amusements in the rural areas included wrestling, hunting, gaming, hawking, fishing, winter sports and the regatta. ‘’ […] here is a very paradise for bear-hunting, deer-hunting, otter-hunting’’ ¹⁴ Mrs Jameson notes in her book – English-born Anna Jameson was wife to the Attorney-General of Upper Canada, Robert Jameson ¹⁵, and throughout her time in Upper Canada she analysed the society and wrote about it. One other important entertainment were dances. They were held frequently, often in barns, with square dance being the most popular ¹⁶. At this point it is important to mention that not everyone had time to participate in these activities, as they had to work their land to make a living. As it was mentioned in an earlier section, some inhabitants never succeeded to make more than needed for their own survival; they simply had not time for amusements.

The lack of time for amusements relates to the saying that ‘’a woman’s work is never done’’ ¹⁷. As Dorothy Duncan describes in her book: ‘’The daily round for women demanded expertise with the fireplace, bake oven, and other utensils as they cooked, baked, put up preserves, heated water for cleaning, laundry, and bathing, melted tallow for candles, and performed a multitude of other tasks, as well as made sure three daily meals were on the table for family, friends, neighbours, and servants’’ ¹⁸. A woman’s daily life was anything but relaxed or boring, as she was continuously busy. This is also something that Mrs Jameson describes: ‘’I am in a small community of fourth-rate, half-educated, or uneducated people, where local politics of the meanest kind engross the men, and petty gossip and household cares the women’’ ¹⁹. Her view might be influenced negatively by the way of life she had been used to before. She had followed her husband reluctantly to Toronto in 1836 ²⁰ – back in Europe she had been an independent career woman, a successful author. ‘’She was naturally not eager for the walk-on part of demure, dependant wife, leaning on a husband’s arm’’ ²¹. However, her description matches that of Dorothy Duncan. So, if they found the time, what did women do in their spare time? Did they have any social life outside their family?

Women’s social life depended on informal visits. Unlike men, they could not take part in the activities mentioned previously. It was not unusual for women to never go anywhere further than ‘’a neighbour’s, the market, or the general store; their lives were often monotonous, for it was usually considered improper for females to enter into the men’s activities’’ ²². This view, of a third source, matches those of Duncan and Jameson, providing a clear division between men and women regarding amusements. Thus, it is safe to say that there was a strict distinction between a man’s and a woman’s (social) life and what was expected of them. It was a traditional way of life, with the men being in charge and enjoying more freedom than women.

Women of a higher social hierarchy, however, did enjoy a more worry-free life and entertaining lifestyle. Mrs Elizabeth Simcoe is an example of this. She was the wife of the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada. In her diary entries, she writes about having dinners ²³ and her expected high standards ²⁴. From her entries it does not seem as if she had to do any household work, unlike the previously mentioned women in rural areas. And this was at a time when Upper Canada was just starting to develop, and everyone had to work hard to make a living and survive. This proves that social hierarchy did matter and influenced a woman’s daily and social life crucially.

- Conclusion

The society of Upper Canada was not further advanced in terms of women’s rights and freedom than any other in that time. Social hierarchy was very important and decided a woman’s daily life and social role. Women of a lower social hierarchy and in the rural areas did not enjoy the same amusements as men and as the women of a higher social class, and were expected to provide for their families without a break. Distinctions between men and women were made both in the daily life, regarding tasks and responsibilities, and in the social life, regarding amusements and entertainment.

- Endnotes

¹ Jane Errington, Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids: Working Women in Upper Canada, 1790-1840 (Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press, 1995), 7.

² Errington, Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids, 13

³ Errington, Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids, 6

⁴ Errington, Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids, 17

⁵ Errington, Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids, 8

⁶ Errington, Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids, 21

⁷ Errington, Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids, 7

⁸ Dorothy Duncan, Hoping for the Best, Preparing for the Worst: Everyday Life in Upper Canada, 1812-1814 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2012), 83.

⁹ Errington, Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids, 14

¹⁰ Edwin Guillet, Pioneer Days in Upper Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1973), 169

¹¹ Guillet, Pioneer Days in Upper Canada, 173-174

¹² Duncan, Hoping for the Best, Preparing for the Worst, 75

¹³ Guillet, Pioneer Days in Upper Canada, 141

¹⁴ Anna Jameson, Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada (London: Saunders and Otley, Conduit Street, 1838), 332-333.

¹⁵ Marian Fowler, The Embroidered Tent (Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 1982), 145.

¹⁶ Guillet, Pioneer Days in Upper Canada, 156-157

¹⁷ Duncan, Hoping for the Best, Preparing for the Worst, 83

¹⁸ Duncan, Hoping for the Best, Preparing for the Worst, 84

¹⁹ Fowler, The Embroidered Tent, 150

²⁰ Fowler, The Embroidered Tent, 146-147

²¹ Fowler, The Embroidered Tent, 148

²² Guillet, Pioneer Days in Upper Canada,152-153.

²³ J. Ross Robertson, The Diary of Mrs. John Graves Simcoe (Toronto: Coles Pub. Co., 1973), 264.

²⁴ Robertson, The Diary of Mrs. John Graves Simcoe, 266

- Bibliography

Duncan, Dorothy. Hoping for the Best, Preparing for the Worst: Everyday Life in Upper Canada, 1812-1814. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2012.

Errington, Jane. Wives and Mothers, Schoolmistresses and Scullery Maids: Working Women in Upper Canada, 1790-1840. Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press, 1995.

Fowler, Marian. The Embroidered Tent, Five Gentlewomen in Early Canada, Elizabeth Simcoe, Catharine Parr Trail, Susanna Moodie, Anna Jameson, Lady Dufferin. Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 1982.

Guillet, Edwin. Pioneer Days in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1973.

Jameson, Anna. Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada. London: Saunders and Otley,

Conduit Street, 1838.

Robertson, J. Ross. The Diary of Mrs. John Graves Simcoe, Wife of the First Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Upper Canada, 1792-6. Toronto: Coles Pub. Co., 1973