In this first chapter the author, John Douglas Belshaw, gives an introduction to history – what is history, how is it made, what do historians do? Also, he analyses how the way history is written, on what it focuses, changes with each generation.

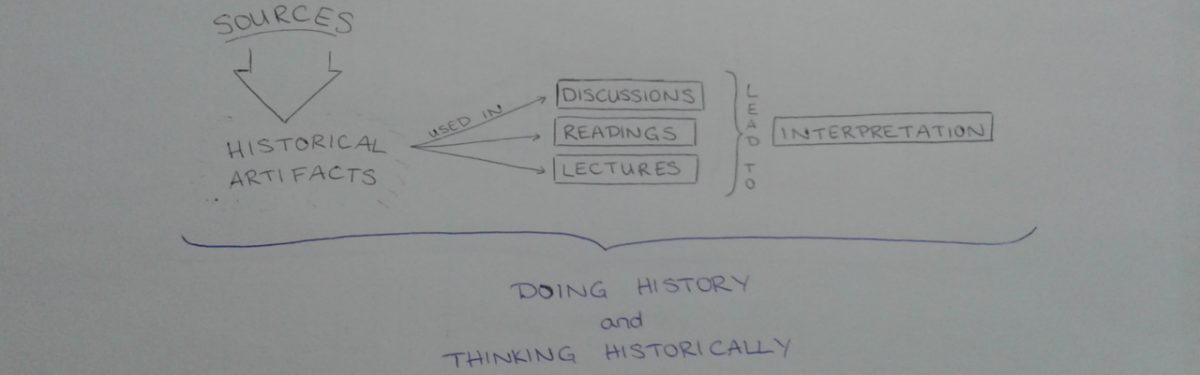

First, he states that reliability and verifiability are the two most important rules for historians when writing about historical events. Secondly, he notes that withholding any information is untypical for a historian, as this would intervene with the previously mentioned rules. Historians make use of two different kinds of sources, which are called primary and secondary sources.

Belshaw reminds the reader that the way we see historical events change within time, as historians gather more and new information and knowledge, either directly through research in that specific field, or by learning about new discoveries in different fields. Also, ideologies and bias can affect our perception of history. This is why the way historians write about history, on what they focus, is not the same as how the previous generation wrote about it.

Belshaw uses several different forms of evidence. Mostly he uses historical examples to back up his ideas and arguments. Also, he quotes other historians and writers at a few text passages. And finally, he uses pictures and paintings as proof, showing them to the reader and explaining how they are linked to what he just wrote.

To me, this chapter is convincing, as Belshaw not only uses evidence, but also wrote the text cohesive. In addition, he does not only give his own opinion, but reflects on the opinions and ideas of others. Every now and then he challenges the reader by asking questions, making me actually think about what he just wrote. All in all, it is a good introduction to history.

Belshaw, John Douglas. ‘’Chapter 1’’ In Canadian History: Pre-Confederation, 2 – 26. Vancouver: BCCampus, 2015